The record-breaking olive harvest makes the Tunisian government rejoice. But voiced concerns of farmers and transformers expose the hidden complexities of a fragile sector and raise questions about its future.

“I believed the olive oil sector would be a promising one, so I invested in establishing this mill in 2004, even though the olive grove I own is not very big.” Slim Hamdaoui, farmer and owner of the oil mill, made this winning bet. His transformation plant in the region of Bejaoua, Manouba (Tunis suburb) is “a natural continuity” of his father’s activity. He not only inherited his the 11 hectares, but also an invaluable agricultural knowhow.

The farmer was already motivated by the prospects of the exceptional harvest that reached 350 thousand tons according to official estimates. Like Hamdaoui, almost two thirds (60%) of the total agricultural exploitations in Tunisia, representing 309,000 producers, extract part or all of their revenues from the groves of olive oil trees.

A bet they placed on the sector, as did the State, by adopting olive oil both as lead export product in its export-led model of growth and as a means to leverage the deficit in the balance of payments.

A Challenging production environment

But the bet does not come without challenges that threaten to bite into farmers’ profit margins. “Labor scarcity is a threat to the harvest” warned Hamdaoui. “We hope there will be enough seasonal workers to cover the farmers’ demand for labor in this abundant season!”.

He explains that every farmer will want to collect his ripe fruits to prevent losses. And as the harvest season only lasts 3 months, the peak in demand for labor caused a shortage in available seasonal workers. “This compels farmers to bring workers from other regions” according to Hamdaoui, driving further an already hiking cost of production.

Watch [Arabic]: Who makes the most out of the exceptional Olive season?

The pressure on the profit margins comes also from the fluctuation of the selling price of olives. Beyond excitement, the signs of abundance have particularly triggered concerns of the farmers from the risk of a drop in selling prices. Far earlier than the season, the biggest farmers’ union UTAP called for the National Olive Oil Office to intervene and regulate the market by absorbing the surplus, and setting a reasonable selling price.

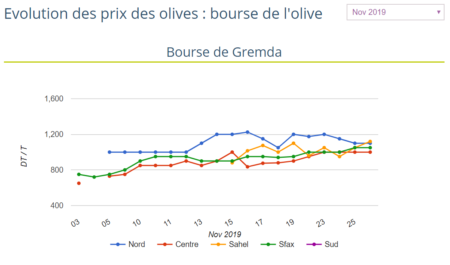

As the season started, the numbers came to confirm farmers’ guess. In the Municipal Market of Gremda (Sfax), the biggest souk of olives in the country and also called the country’s “Olive stock market”, the season kicked off with an entry price of 0.75 TND or $0.25 for the kilogram of olive. Never a starting price has been as low in the last 5 seasons, according to the data on the National Oil Office website.

For Abdallah Ameri, olive producer in Beja and secretary-general of the Association of Tunisian Farmers for Orientation and Development, this market price is far below farmers’ expectations. It barely exceeds the costs of labor, energy, machinery rent for plowing that farmers have to pay throughout the year.

And despite a general increase in the price trend, the aggregate price shown in the graph do not portray all experiences. In the first week of December, in different regions of Kairouan, farmer protests erupted, and a national road was blocked as the price of the Kilogram fell to as low as 0.5 TND according to declarations. Interviewed by local radio Sabra FM, a protesting miller complained: “the price fell from 6 to 4.7 TND/kg in a matter of two days. It is not normal, it is unbearable.” He blames the exporters, the price setters in the market, for manipulating the prices.

A sector under predation

“It is very easy to infiltrate the chain and manipulate prices” For Mokhtar Boubaker, head of the Synagri in Manouba. This unionist explains that there is a growing phenomenon of predation in the sector.

“Usually, the distribution works as follows: farmers harvest their fruits and sell to olive mills, who later sell to exporters. These intermediaries, often coming from the unregulated sector with limitless resources, position themselves between farmers and olive mills. They suggest to buy the farmer’s harvest ahead of season and to take in charge the costs of labor and transport.”

Boubaker describes the negotiations about selling prices as a deceptive game. “Every year, since the beginning of the season, we would hear that the prices are going to fall. But these are only rumors spread by intermediaries. They play with the fears of farmers and exploit their indebtedness and vulnerable financial situation to push down the buying price. They later sell the harvest to olive mills at market prices. These people are totally “strangers” to the sector. However, their purchase capacity confers them a lot of power.”

This will not be the only story of price manipulation we would hear. An expert in ONH confirms the vulnerability of the sector to infiltration. He relates the story of the 2017 shock, or what he called a “2017 money laundering operation”. “Two years ago, the sector was a victim of the speculation of new actors coming from the unregulated sector. These people used the intermediation between the farmer and the oil-mill in a money-laundering operation.”

The deceptive game of price-setting comes back in this story too. “These actors offered to buy farmers produce at very interesting prices, above the real market price, ahead of season. As communication in the market flows rapidly, no farmer wanted to sell below that price. This drove the general market price up and forced oil mills to buy from farmers at the new price too.”

However, the price at which olive mills sell to exporters in not determined locally. “Then the news about the international price came. The price revealed lower than the costs for olive mills. This triggered a shock. Millers were forced either to sell the pressed oil to exporters at loss or to keep it in stock until they can find a better liquidation opportunity. The price shock resulted in many of the oil-mills defaulting on loan payments and going bankrupt, or compelled to sell property to reimburse.”

Asked about the reason why these actors would sell to olive mills at no gain or loss, he answered that “these people do not care if they lose in the process, as long as they can bring back a share of that money to the formal sector”

In 2019, two seasons later, debt still burdens almost 50% of the country’s oil-mills, according to the declaration of Mohamed Nasraoui, the head of the National League of Olive Oil producers, on Shems FM. He explains that this burden is creating resistance from transformers to buy farmers’ produce, and pushing farmers to give up the harvest, in the absence of the National Olive Oil as an alternative buyer.

“The Olive oil office played a historical role decades ago in regulating the market. However, this belongs to the past” Mokhtar Boubaker blames the state leaving the sector and the producers to “the unknown”. He argues that there is no clear policy to support and orient such an important sector.

The rest of the farmers and olive mills expect an intervention. However, to date, the National Oil Office did not start regulating the market yet.

The State, and the long-awaited intervention

Since the beginning of the season, actors in the sector called on the State to intervene. Farmers unions demanded the absorption of the excess of production to regulate the prices and allow decent benefits to farmers. They also asked for authorities to a bottom selling price for olives at the farms. On the other hand, millers organization, still suffering the 2017, requested the State to support their demand for the rescheduling of their loan payment deadlines to the end of the season.

Contacted at the beginning of the season, the expert of the National Oil Office explained that their institution cannot take in charge the losses of other actors in the sector. “Since the 90s, the State decided to give up its monopoly of the sector and liberalize it. Private businesses were allowed to import and export. From that date, the National Oil Office became equal to any other private actor in the market. We are financially independent and we have to make sure we are not in deficit. If we are going to intervene, who is going to compensate for our financial imbalance?”

The Ministry of Agriculture announced a set of decisions to support the sector, among which is a governmental plan to transfer funds to the National Oil Office to insure what farmers impatiently wait for: the beginning of market regulation.

However, this set of decisions taken by the Ministry at the end of November remains “far below producers expectations” according to a statement released by the farmer’s union (UTAP) on December 3rd.

The series of governmental measures also include the rescheduling of loans of Oil exporters and Olive mills and the elimination of the payment delay penalties. The Parliament approved in the 2020 finance law a tax cut to allow an equivalent compensation of banks for the dropped penalties.

This promises to encourage the mills to resume their buying activity, and restore smoothness to the chain. But protests of producers, who are not touched by this measure, continue.

Mohamed Haddad & Khansa Ben Tarjem reviewed this article. Mohamed Alyani contributed reporting.

اضف تعليق